I stopped writing these for a hundred reasons, the latest and bleakest being fear of plagiarism or impersonation by robots. Instagram and Strava serve well enough as low-effort logbooks, for all their dark magic. I keep a scattershot private journal, too.

But I remain incurably devoted to remembering, and I can’t deny that the things I bother to put here, to stitch together neatly enough for a hypothetical reader, are what I remember—or at least feel I remember—best:

You write a thing down because you’re hoping to get a hold on it. You write about experiences partly to understand what they mean, partly not to lose them to time. To oblivion. But there’s always the danger of the opposite happening. Losing the memory of the experience itself to the memory of writing about it. Like people whose memories of places they’ve traveled to are in fact only memories of the pictures they took there. In the end, writing and photography probably destroy more of the past than they ever preserve of it.

Sigmund Nunez, The Friend

Even if writing is destructive, and reading conjures nothing but phantoms, I’d rather have these to turn to than nothing at all. I don’t understand live-laugh-love exhortations to just “be in the moment.” If the moment’s any good then I want to take notes so I can have it forever; if it’s not then I’d rather go somewhere else.

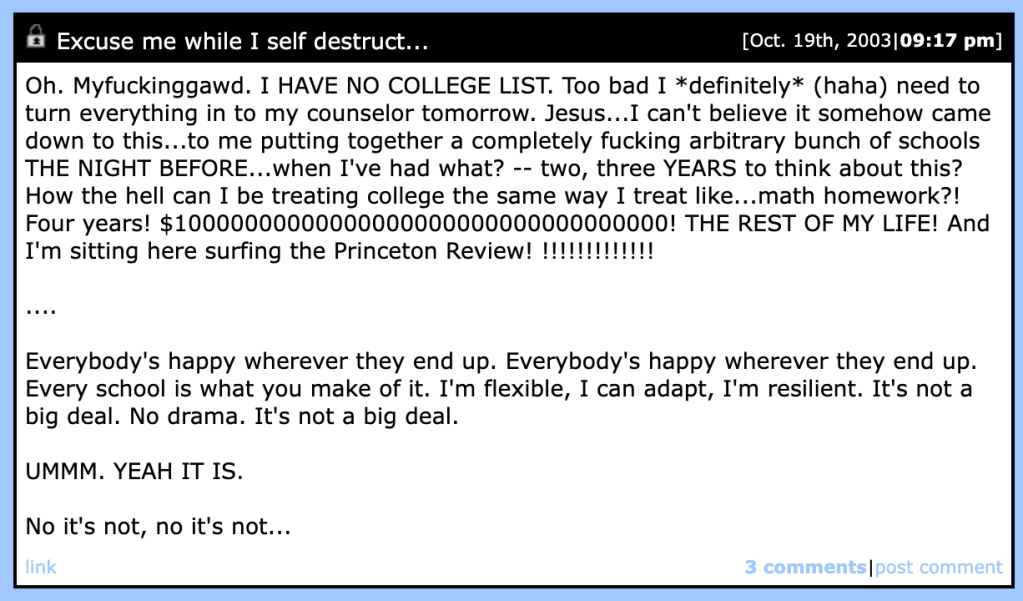

Consequently I’ve kept boring blogs on-and-off since middle school. Their contents are mortifying but useful to me in many ways, and even if they weren’t I don’t imagine I could help myself. I was born a magpie, a compulsive collector, and I’m lucky to have confined the habit (more or less) to memories and rocks. I am a few twists of the gene away from a starring role on “Hoarders” and I know it.

But the gathering and gardening is getting harder. Because the various disruptions of the COVID era coincided with my limping into middle age, it’s hard to know whether to blame time or the times for having become gallingly forgetful. I’m dogged daily by the cruel phenomenon of remembering that I wanted to remember something—even where I was and what I was wearing at the time—but not the thing itself. Sometime during peak pandemic I gave up and activated Siri, setting aside my mistrust of surveillance capitalism for the convenience of issuing “remind me” commands to the empty air. Alas, all I have to show for the trade is a list of baffling fragments, stripped of any context and hundreds of items long.

I forget that I’ve made tea, what I opened a new tab for, where I put my keys. A friend joined the ranks of those medicating for anxiety and asked why I still refused to do the same, even having finally conceded that it might not be Normal® to envision your own death 28 times a day. I have balked at every flavor of pharmaceutical my entire life, but I found I had no answer to the question. It was days before it re-occurred to me that I couldn’t accept the risk of dependency—that is to say, I had forgotten my own defining, existential fear.

Point being: anything I want to remember, I probably do have to write. But like deferred maintenance in any other context, the backlog on this thing has become so overwhelming it’s impossible to address within the constraints of my own completionism. A thousand words each for dozens of inane little roadtrips is an obvious impossibility.

So, a catch-up compromise: blurbs, and only for firsts and other biggies. One year at a time. I think I can!